my document: US strategy to ‘dethrone’ Putin for oil pipelines might provoke WW3

Senior DIA, Air Force and Army officials admit that NATO expansionism and US covert interference in Russian internal politics may trigger “next global conflict”

By Nafeez Ahmed

Published by INSURGE intelligence, a crowdfundedinvestigative journalism platform for people and planet. Support us to report where others fear to tread.

A US Army document concedes the real interests driving US military strategy toward Russia: dominating oil pipeline routes, accessing the vast natural resources of Central Asia, and enforcing the expansion of American capitalism worldwide.

The Russians are coming. They hacked our elections. They are lurking behind numerous alternative political movements and news outlets. Such is the overwhelming chorus from traditional reporting on Russia, which sees the United States as being under threat from fanatical Russian expansionism — expansionism which has gone so far as to interfere dramatically in the 2016 Presidential elections.

Russia is certainly an authoritarian regime with its own regional imperial ambitions. President Vladimir Putin and his cronies are responsible for massive deaths and human rights violations against populations at home and abroad (the latter in war theaters like Syria and elsewhere). Putin has strengthened a system of oligarchical state-dominated predatory capitalism which has widened extreme inequality and concentrated elite wealth. And we will no doubt learn more about what shenanigans Russia did, or did not, get up to in relation to US elections.

For the most part, these are not especially dangerous things to report on from the comfort of the West. Somewhat lacking from conventional reporting, on the other hand, is serious reflection on whether US policies toward Russia have contributed directly to the deterioration of US-Russia relations.

While the bulk of the Western pundit class are busy bravely obsessing over the innumerable evils of Putin, it turns out that the upper echelons of the US military are asking some uncomfortable questions about how we got to where we are.

A study by the US Army’s Command and General Staff College Press of the Combined Arms Center at Fort Leavenworth reveals that US strategy toward Russia has been heavily motivated by the goal of dominating Central Asian oil and gas resources, and associated pipeline routes.

The remarkable document, prepared by the US Army’s Culture, Regional Expertise and Language Management Office (CRELMO), concedes that expansionist NATO policies played a key role in provoking Russian militarism. It also contemplates how current US and Russian antagonisms could spark a global nuclear conflict between the two superpowers.

The document remains staunchly critical of Russia and Putin, but finds that Russian belligerence cannot be understood without accounting for the context of ongoing US interference in what Russia perceives to be its legitimate ‘sphere of influence.’

Simultaneously, the document admits that far from the US being some innocently hapless victim of Russian interference, the US has at various times run covert “information, economic and diplomatic” campaigns to either “dethrone Putin”, or at least undermine his rule.

An irony of the document is that despite repeatedly recognizing NATO’s own role in provoking Russian militarism, the US Army study refuses to contemplate a fundamental change of course with respect to NATO policies and interests.

The document contains the usual caveat included with these sorts of internal US military studies, noting that its findings represent the views “of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the Department of the Army or the Department of Defense.” Yet in its foreword, Major General John S. Kem, Commandant of the US Army War College in Carlisle, notes that the volume’s insights “are important for Army professionals who lead Soldiers in a variety of missions across the globe”, and should be considered “by planners and policymakers alike.”

Titled Cultural Perspectives, Geopolitics & Energy Security of Eurasia: Is the Next Global Conflict Imminent?, the study — which was published in March 2017 and has not been reported publicly until now — pinpoints the roles of competing US, European and Russian energy interests in driving growing tensions which could convert regional flashpoints into the next world war.

“Russia’s strategic change is driven mostly by its concern over the NATO’s expansion at the expense of former Warsaw Pact countries (Eastern Europe) and former Soviet republics (Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania),” writes the study’s lead editor and key contributor, Dr. Mahir J. Ibrahimov, Program Manager at the US Army’s CREMLO.

Ibrahimov was previously the Army’s Senior Culture and Foreign Language Advisor, and instructed US diplomats in language and cultures at the State Department. He had many years prior served in the Soviet Army, witnessing the break-up of the USSR.

In the US Army study, he notes that “relations between the West and Russia have deteriorated to their lowest point since the end of the Cold War, eroding global geopolitical stability and damaging trade and economic relations between major global and regional powers.”

But, he writes, official Russian documents including its National Security Strategy and military doctrines show that the driving force behind Russian militarism “is responsiveness to NATO expansion. This is the core principle which is driving Russia’s strategic efforts in the region and beyond.”

Protecting pipelinistan

And what is driving NATO expansionism? While the US Army study highlights concerns about Russian authoritarianism, it remains surprisingly candid in flagging up US energy interests as the primary issue:

“Perhaps the most important reality and rationale for US/Eurasia policy at the time [1990s], however, was the increasing global interdependence in energy and trade,” writes Ibrahimov.

“Vast reserves of oil and natural gas in and around the Caspian Sea were the primary source of the US’s initial interest in the region. That interest could provide the foundation for stronger ties between the US and regional states, with the US providing protection to ensure regional stability and the political independence of the littoral countries.” (p. 8)

Humanitarian intervention and military peacekeeping operations in the region, then, have always had a broader geostrategic agenda related to the “protection” of US access to Caspian oil and gas.

The study points out that US efforts to resolve the Azerbaijani-Armenian conflict, for instance, were less about concerns for peace and human rights than “US and Western countries’ economic and strategic interests in Azerbaijan.”

Ibrahimov notes that “a consortium of Western oil companies, five of which were American, signed a $7.5 billion oil contract with Azerbaijan”, proving the latter’s welcome “commitment to a market-oriented economy, and its firm intention to join the international economic system.”

Equally, Azerbaijani oil was a key motivating factor behind Russia’s invasion of Chechnya. While US and Western companies, the study reports, “had been considering several possible routes for the future pipeline,” Russia wanted the pipeline to run though its own and Chechen territory, undermining “American and Western commercial interests in this region… Russia already had such a policy in the case of Kazakhstan, where American oil companies were also involved (i.e., Chevron),” adds Ibrahimov. (p. 10)

The geopolitical pipeline competition was ultimately won by the United States.

In a section titled, ‘Pipeline Politics and its Regional and Global Implications’, the US Army study notes that the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) pipeline — running from the Azerbaijani capital of Baku through Georgia toward the Turkish port of Ceyhan — “was the first major pipeline to bypass Russian territory.”

Transporting up to one million barrels a day to world markets, the pipeline’s core strategic implication is to:

“… strengthen the political and economic independence of the countries of the region from possible resurgent Russian ambitions. But even before its completion, it had also marked the beginning of the new ‘Great Game’ with global and regional powers such as the US, China, and Russia vying for influence in the area. Once again the region became very attractive for global geopolitics, enhanced by the discoveries of natural resources in Afghanistan such as natural gas, oil, marble, gold, copper, chromite, etc.”

The study also admits that US interests in Afghanistan were preoccupied with the country functioning as a gateway to Central Asian oil and gas reserves:

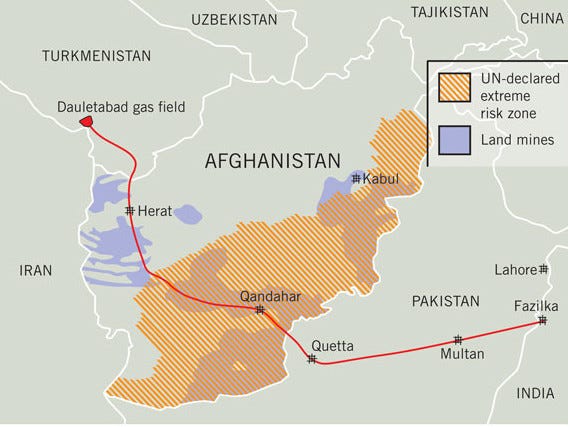

“At the same time, Afghanistan’s significance stems from its geopolitical position as a potential transit route for oil and natural gas exports from Central Asia to the Arabian Sea. This potential includes the possible construction of oil and natural gas export pipelines through Afghanistan, which was under serious consideration in the mid-1990s. The idea has since been undermined by Afghanistan’s instability.”

Nevertheless, the Trans-Afghan oil pipeline project, known as TAPI for its route through Turkmenistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India, has been negotiated and pursued by every single US administration since Clinton.

It finally began construction last month under Donald Trump’s presidency.

The document quotes testimony from former US Ambassador James Maresca, who also served as Vice President of International Relations at oil company UNOCAL, then the principal corporate backer of the TAPI pipeline. Ibrahimov recalls that he was privy to high-level State Department discussions on the policy at the time:

“During my diplomatic service in Washington DC and Ambassador Maresca’s tenure at the Department of State, we had numerous discussions on the issues of pipeline politics and US policy in the region.”

What the document does not acknowledge is that the US government’s commitment to the TAPI pipeline was, at that time, premised on a Taliban victory – a policy that backfired rather catastrophically – as I had documentedhalf a year before 9/11.

‘Awash’ in natural resources

A particularly extraordinary contribution to the US Army study is a section authored by Ambassador Richard E. Hoagland, who retired last August from the post of US Co-Chair of the Organization for Security and Cooperation’s Minsk Group. Previously, he was Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asian Affairs, having served in various diplomatic capacities in the region since the early 1990s.

Among US strategic objectives in Central Asia, Hoagland lists preventing terrorism, stabilizing Afghanistan, preserving the “independence” of the Central Asian republics, promoting good governance, and the following:

“… safeguard US economic interests and continue to promote economic reform so that the five nations can be better embedded in the global economy.”

Underscoring the centrality of US economic interests, Hoagland extolls a wealth of detail on the region’s abundant energy, mineral and raw material reserves:

“But also, the region is awash in natural resources. Turkmenistan has the fourth-largest natural-gas reserves in the world. Kazakhstan has the second-largest oil reserves of the former Soviet Union, second only to Russia, and US and European international oil companies early on made major investments there that continue to this day. Uzbekistan is a major producer of uranium, as is Kazakhstan, and has large natural-gas reserves, as does, quite likely, Tajikistan. Both Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan hold significant gold deposits. In addition, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan have world-class hydropower potential, as demonstrated by the current casa-1000 project to deliver their summer-excess hydroelectricity across Afghanistan to electricity-starved Pakistan.”

These countries, then, are ripe for political integration into the US-dominated market economy:

“To add a bit more nuance, the economies of Central Asia are more than the sum of their natural resources and energy-generating potential. Kazakhstan’s early commitment to macro-economic reform has, 20 years later, created a financial-services hub for the region. Uzbekistan’s educated population of about 30 million has a real potential to provide entrepreneurial and innovative economic growth.” (pp. 28–29)

Despite Hoagland’s obligatory lipservice to ‘good governance’ and ‘civil liberties’, neither feature in any meaningful sense in NATO’s priorities. The Central Asian republics are among the most repressive, anti-democratic regimes in the world, consistently lambasted by human rights organizations for their horrific torture and persecution of any political dissent. ‘Democracy’ promotion clearly does not mean actual ‘democracy’ — it simply means a geopolitical alignment with NATO, hostility toward Russia, and an opening up of the economy to US and Western foreign investors, human rights be damned.

The intransigence of independence

Against this backdrop, a principal motivator for US hostility toward Russia is the latter’s consistent effort to integrate interested countries into alternative regional political and economic structures.

“Estranged from the West over NATO Expansion, and especially because of the situation in Ukraine, which led to the Western sanctions, Russia seeks closer economic and political rapprochement with China,” observes lead editor Ibrahimov:

“Russia is currently seeking to create security and economic organizations that could be used to rival the existing structures such as NATO and the World Bank. Russia, China, Iran, and other countries have undertaken these and other steps which are not in the national security interests of the United States.”

The core challenge from Russia, the US Army study implies, is its leadership role in building alternative coalitions to US-dominated political and economic systems. The coalition of new alliances that have emerged as a result — the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), the coalition of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS), the Eurasian Customs Union (ECU) — “are mostly aimed at opposing US economic and strategic dominance”, the document remarks.

Opposing US dominance appears to be a cardinal sin for US military strategists:

“It is obvious that Russia-China rapprochement presents a profound challenge to the United States. The realpolitik question for US policy makers would be how to prevent this historically unlikely alliance between the two major global and regional players.”

A major priority, then, for US geopolitical strategy is how to break apart these alliances and coalitions between US rivals, which challenge “US economic and strategic dominance”.

One useful mechanism is the nuclear card, which contrary to conventional opinion, has been played far more recklessly by the West than Russia.

NATO provocation heightening threat of global nuclear war

There has been much coverage recently of how Putin poses a grave nuclear threat to the US and the world.

Yet this has ignored the context of Russia nuclear saber-rattling in persistent NATO provocations, as highlighted in a separate chapter in the US Army study exploring how Russian militarism is consistently a response to NATO nuclear expansion.

The section is authored by Colonel Lee G. Gentile, Jr., Vice Commander of the 71st Flying Training Wing at Vance Air Force Base, Oklahoma. He was previously lead operational planner at the Air Forces Central Command Combined Air Operations Center, and went on to serve in Iraq.

According to Col. Gentile, a co-editor of the US Army study, the origin of Russian paranoia about Western intentions goes back to the early 1950s, when the US adopted the ‘First Offset’ strategy by which it “threatened a nuclear strike in order to ‘convince’ the Kremlin that fighting another world war was not beneficial to the Soviet Union.”

In other words, it was the US that initially threatened the Kremlin with a nuclear first strike policy.

The US Army study acknowledges, however, that:

“Recently declassified Soviet papers, articles, and meeting minutes indicate that the Soviet leadership had no intention of invading Europe.”

That is contrary, it should be remembered, to the official state propaganda at the time, parrotted dutifully by the Western press.

After the experience of the world wars, Russia feared that the West would invade if the USSR was too militarily weak, fears compounded by Western advancements in nuclear weapons technology:

“Therefore, the Soviets developed and tested a nuclear device in 1949 in order to counter the West’s advantage.”

The West then upgraded its nuclear weapons policy. In 1954, the Eisenhower Administration adopted the ‘New Look Policy’ to maintain “a smaller, more-capable, forward-deployed, conventional force that was reinforced by the massive retaliatory power of nuclear weapons.”

Unsurprisingly, this in turn “furthered Soviet fears of Western aggression… Soviet leaders believed that Western deterrent actions were offensive not defensive, and were designed to ‘compel’ Soviet leaders to accept Western political demands.”

In more recent times, US and NATO military expansion was similarly a principal factor in Russian nuclear saber rattling, according to the document.

The US now possesses “global precision-strike capability”. Faced further with “a combined 1.4 million-man NATO military force to the west and a 2.3 million-man Chinese army to the south,” if the Kremlin was to try to “counter the threat conventionally”, its defense spending would reach “unsustainable levels.”

This “helps to explain why the Kremlin is using its nuclear arsenal as a strategic reserve to protect its smaller conventional force while relying on unconventional and asymmetric methods to secure national interests.”

To that extent, Russian belligerence is in some ways a rational strategic response to the perception of NATO imperialism:

“Simply put, Russian leaders want to limit the expansion and influence of NATO, create a buffer between Russia and NATO, re-establish its influence in former Soviet states, and return to being a regional and global power.”

Russia is also “paranoid about a surprise attack from NATO or the US”, a fear which stems from “the German invasion of western Russia during Operation Barbarossa” as well as “US and NATO operations in the Caucuses and the Middle East.”

“When viewed from the Russian standpoint, these fears are understandable,” observes the US Army study, noting that relentless NATO encroachment along Russia’s borders has pushed Russia into a corner in which playing the nuclear card to attempt to deter NATO is its only option:

“Considering that NATO was created to counter the expansion of the Soviet Union, it is not surprising that the Kremlin views expansion as a threat. Every time a former Soviet state is incorporated into NATO, the buffer shrinks. Without that physical buffer, Western military forces move closer to Moscow, eliminating the Kremlin’s ability to trade space for time. Similarly, missile defense erodes the Kremlin’s most powerful strategic and political weapons, its nuclear-tipped ballistic missiles. From the Kremlin’s perspective, the West is willing to attack any ‘disruptive’ country that lacks nuclear capability in order to ‘force its political will’ on international and regional affairs. Therefore, the Russian leadership views its nuclear weapons as its most important political tool because they would have limited to no ability to affect regional and international affairs without them.”

The document goes on to compare NATO policy to co-opt former Soviet states to an imagined Russian effort to incorporate Mexico or Canada into the Warsaw Pact, or deploy ballistic missile defences to the Americas — such actions have never been contemplated by Russia, and would of course never be acceptable to the United States. But, the document says, their equivalence in Eastern Europe and Central Asia is already being carried out by NATO to weaken Russia. This is why the incorporation of Georgia into NATO “triggered the 2008 Russian invasion of South Ossetia and the Kremlin’s first use of nuclear coercion.” (p. 87)

Based on this analysis, the study advocates more concerted efforts by the West to engage Russia constructively, with a view “to develop a shared understanding of the situation before it leads to a stalemate.” This might “reduce tensions without pursuing actions that the Kremlin will view as threatening.” This recommendation, though, comes with the following stark warning:

“Without dialogue, the risk of another Cold War and possible nuclear confrontation is high.”

Russian regime change?

There is another context to Putin’s paranoid nuclear pronouncements — the justified fear of Western efforts to shape Russian politics.

Unfortunately, the sober and self-reflective analysis contained in some parts of the US Army study is accompanied by aggressive posturing attempting to justify an active policy of US interference in Russian economic and political affairs.

Yet this material is significant precisely for confirming the extent to which the US is willing to interfere in Russia’s internal affairs.

The US Army’s lead culture analyst Dr. Ibrahimov points out that after the Soviet Union’s collapse, the US government “developed a program with the purpose to enhance democracy and free markets in the republics of the former USSR.” The program was inaugurated through the Freedom Support Act of 1992, committing $12 billion to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to facilitate the former Soviet states and Russia moving to “the path of democratic and free market reform.”

While one motivation was to avoid threats from “possible future totalitarian regimes”, the other was blatantly self-interested:

“… an economically open and growing FSU would likely have significant trade and investment benefits for the United States.”

Ibrahimov further observes that through these policies, the US actively attempted to nurture specific Russian political leaders considered amenable to US interests:

“… reliance on personalities, rather than basic principles, in US dealings with Russia tied the future of American interests to the political viability of certain Russian politicians.” (13–14)

A section by study co-editor Gustav A. Otto, Distinguished Chair for Defense Intelligence at the US Army Combined Arms Center and Chief of Training at the Pentagon’s Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), elaborates on how this US strategy of political interference plays out today, with several references to an active covert regime change strategy against Putin.

Otto wavers between dismissing the viability of such a strategy, and recognizing its necessity in some form, eventually settling on the notion that while a direct military effort to oust Putin is out of the question, covert mechanisms may be more acceptable.

“Trying to get rid of Putin probably isn’t the answer,” the US Army study observes. “We need look no further than the lineage of his predecessors, or we can look at the case studies of Iraq or Libya. Knocking the king off his throne is nice in fairy tales, but doesn’t seem to work in the real world.”

And yet, the document observes that Russia:

“… may soon feel the pressure of the domestic downturn. They will become increasingly vulnerable as the ruble weakens and the purchasing power at home erodes. Are the West and the US poised to take advantage of this, or will we miss another opportunity?” (p. 103)

What does “taking advantage” actually mean? The document appears to suggest interference in Russia’s forthcoming elections:

“With the 2018 Russian presidential elections, watch for a fourth-term bid by Putin, then look for possible changes to allow more. How to start thinking about it — be deviant and do not forget the old ways. The key is creating a strategy of one’s own, not an ‘anything but’ strategy as Russia appears to have. It will be reactive to a degree, but should focus on putting Putin off balance, without becoming too defensive… The US and the West need to determine what they want Russia to look like, how they want it to behave and if they care if Vladimir Putin is president.” (p. 106)

At no point does Otto recognize the imperial irony in Western leaders believing they have any right whatsoever in determining what Russia should look like. Instead he says:

“As the US and the West wrestle with what they want Russia to look like, they would be well served to pursue a tiered strategy of appeasement, persuasion, and deterrence without seeking to escalate already bloody friction points.”

He doesn’t quite seem to understand that the assumption that the US should be able to shape Russian politics and economics through a “tiered” carrot and stick “strategy” might be a principal cause of escalating those “friction points.”

Along these lines, the document openly acknowledges that US policy is already actively intervening in Russian politics.

Noting that one potential strategy is to “dethrone Putin” through a covert political campaign, rather than any overt intervention, the US Army study remarks that this strategy has already been executed in “fits” and “starts” by the US and, intriguingly, other Western countries:

“Another possible strategy option for the US would be to seek to dethrone Putin, in hopes of a more cooperative successor. Rather than Iraq-like military ousting, the US and the West could drive a cohesive information, economic and diplomatic campaign helping Putin’s supporters choose a new leader… This strategy seems to have fits of starts and stops by the US and several others in the West. Putin is a master at navigating these kinds of threats, and almost seems to invite them, knowing this is a game he excels at. An anti-Putin campaign probably isn’t what the US and the West really want. Rather, it is to minimize new aggression and mitigate behaviors to date.”

With that in mind, the document also sets out more conciliatory gestures to appease Russia, for instance, in “negotiations on any of the frozen conflicts the US, the West and Russia are involved in… One notion might be a bigger role with Iran, Syria or even Turkey.”

This does, indeed, now appear to be the self-serving policy adopted in Syria, where the US is actively planning for an accommodation with Bashir al-Assad. In the words of the DIA’s Otto, “there must be an understanding that some countries may suffer as a result of our actions. A strategy of partial withdrawal from Syria or the Ukraine may actually allow for better future negotiations. The springtime drawdown of Russia from Syria allowed negotiation space for Putin, and even Assad.”

Despite this, the document adds a barely veiled threat amidst this more diplomatic language:

“Putin is rational and he isn’t weak… yet. However, the recent economic turmoil, the frailty of the petrol industry, and a struggling domestic agriculture may eventually force him to address some of these issues. Bread lines in Russia are growing and shelves are becoming barer. We should be ready to strike when that time comes, and it is coming.” (p. 107)

This story was 100% reader-funded. Please support our independent journalism for as little as $1 a month, and share widely.

Dr. Nafeez Ahmed is the founding editor of INSURGE intelligence. Nafeez is a 16-year investigative journalist, formerly of The Guardian where he reported on the geopolitics of social, economic and environmental crises. Nafeez reports on ‘global system change’ for VICE’s Motherboard, and on regional geopolitics for Middle East Eye. He has bylines in The Independent on Sunday, The Independent, The Scotsman, Sydney Morning Herald, The Age, Foreign Policy, The Atlantic, Quartz, New York Observer, The New Statesman, Prospect, Le Monde diplomatique, among other places. He has twice won the Project Censored Award for his investigative reporting; twice been featured in the Evening Standard’s top 1,000 list of most influential Londoners; and won the Naples Prize, Italy’s most prestigious literary award created by the President of the Republic. Nafeez is also a widely-published and cited interdisciplinary academic applying complex systems analysis to ecological and political violence.

No comments:

Post a Comment